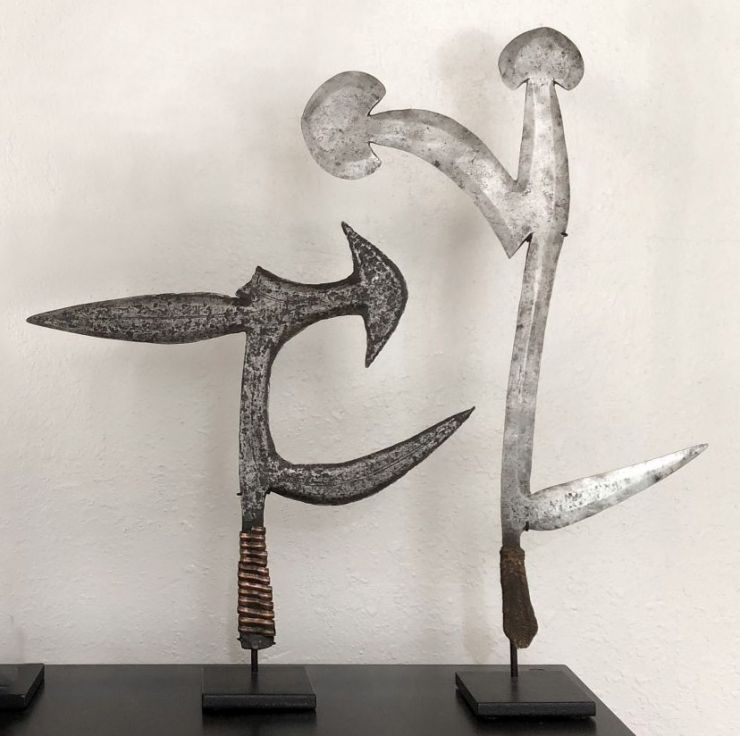

Throwing African Throwing Knives

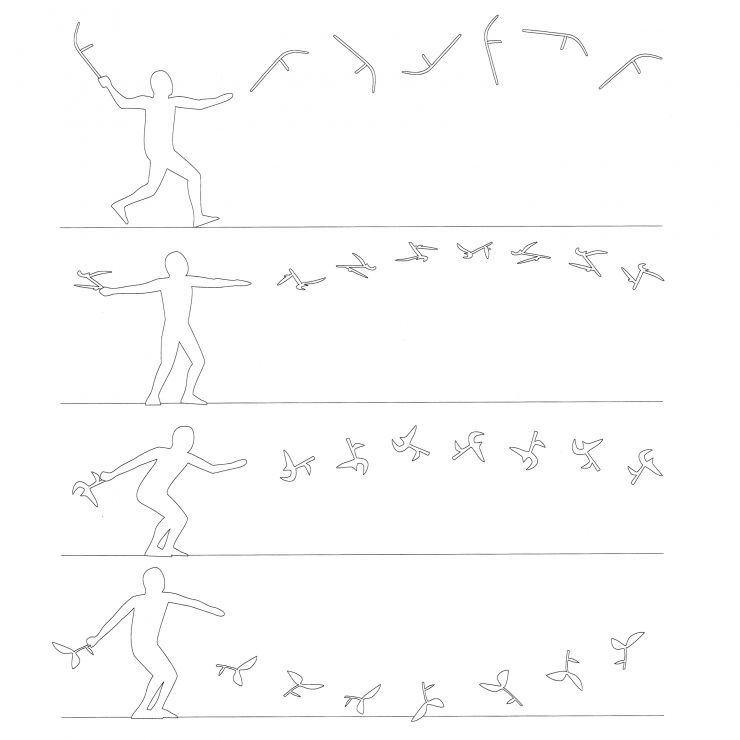

I was in the middle of negotiating the sale of an Ngbaka-Mabo throwing knife years ago, when the buyer asked me how well the knife he was buying flew. I pointed to a few references that described the way in which this type of knife was supposed to be thrown and how well it would fly, and showed him illustrations like this:

(Illustration from: Felix, Kipinga, 1991)

But those hypothetical answers didn’t answer his question. He wanted to know how this specific knife took to the air. Eventually, he agreed to buy the Mabo from me, but only if I first threw the knife to test my assertions about its flight characteristics. I took it outside to my backyard and launched it into the grass with a short, delicate sidearm throw, ensuring that I wouldn’t damage a piece that I had just sold.

It flew through the air surprisingly well, exceeding my expectations. While this one small toss augmented my knowledge about the way in which these weapons functioned, it was my only foray into physically testing one.

I have been in the business of buying and selling African throwing knives as works of art for years, and it struck me recently that I haven’t done much to understand them as functional objects. So, I decided to begin a series of tests that would allow me to understand these objects in a new light — throwing them with force and intent, as they would have been used in their original context.

Obviously, this undertaking involved some risk; Launching of one of these knives can very well cause its destruction. Many of the knives I chose for this test were created over a century ago, so damaging or destroying them was a possibility I hoped to avoid but had to entertain. In fact, this risk is part of the knives’ identity, being expensive and time-consuming to produce. Westerdijk wrote (describing Ngombe knives) that because of the value of a throwing knife, “its owner hurled it only in the last resort, or when he esteemed to have a fair chance of recovering it” (The African Throwing Knife, 1988).

On a sunny day in June, Tim Hamill, Matt Mrachek, and I took a dozen throwing knives out to a large, open backyard (about 30 yards long) and threw each knife with multiple full-power throws. After these flight tests, we also threw the knives at a tree from only five yards away, to test their sticking/stabbing potential.

I chose 12 throwing knives from various African cultures for testing: 1 Teda/Sara, 1 Kare, 2 Laka, 2 Nzakara, 2 Western Banda, 3 Ngbaka Mabo, and 1 Ngombe. Each knife was thrown with three different motions: along the vertical axis (overhand), along the horizontal axis (sidearm), and freestyle (whatever seemed comfortable).

Group 1 – F-Types

Laka:

We threw two similar Laka blades of the large and heavy style; the notion that we would be throwing them any great distance seemed improbable. It was immediately obvious that anything but an overhand throw would be ineffective. We had a good deal of trouble controlling the flight path, which leads me to the conclusion that compared to the other knives we tested, it would be more difficult to hit a target with these, but if you did, the damage would be catastrophic.

Despite their unsharpened edges, these blades often landed stuck into the ground, and one remained stuck into our test tree. Because of their substantial size and weight, they required considerable force to achieve a strong throw, especially one that traveled farther than 20 yards.

Teda / Kare:

Predictably, as the Teda and Kare throwing knives are stylistically related to the Lakas, throwing them required considerable force, they were most effective thrown overhand, and many of them landed stuck into the ground. Because they are made from higher quality iron, weigh less, and have sharper edges, we observed a faster in-flight rotation of the blade and longer flights (of 20-25 yards). While their accuracy was better than the Lakas, it was clear that these knives would still be most effective and cause the most damage in close proximity to a target.

Group 2 – Z-Types

Nzakara:

The Nzakara knives used in our tests are reputed to be some of the most dangerous of all African throwing knives. However, both of the examples we threw had no handle grips, and the iron on the handles was notched – a detail designed to hold the grip in place. The substantial piece of iron combined with the notched handle caused our best throws, launched sidearm, to spin fast briefly, but then float to the ground gently like a frisbee within 15-20 yards. While we were able to throw four F-types of similar weight effectively without any handle grip, the absence of a grip and the notched iron edges on the Nzakaras rendered them ineffective weapons.

Group 3 – Compact throwing knives

Ngombe / Ngbaka-Mabo:

The performance of these two types was very similar, hence their grouping here. These were the most compact knives we tested, and they left the hand very comfortably and flew naturally. They flew most effectively with a sidearm throw, especially when the thrower was able to keep the trajectory parallel to the ground; this formula produced accurate throws that travelled 25-35 yards.

With a loftier or a non-sidearm throw, the knives still flew extremely well, yet became wildly inaccurate. A Mabo thrown at 45 degrees sliced wildly and ended up trapped in a tree branch 30 feet off the ground (we later recovered it).

Banda:

The two Banda throwing knives gave us the surprise of the day, because of how easily and naturally they flew. They were the lightest knives we tested, and small and compact like the Mabos. They weren’t effective thrown overhand, but with a sidearm throw, they flew with great efficiency and accuracy at 30-40 yards. Similar to the Mabos, there was a specific formula that generated an accurate throw that could strike a target with force at distances beyond 30 yards: a sidearm throw with a quick rotation and a trajectory parallel to the ground. When they were launched with a semi-sidearm throw, they moved erratically, yet still traveled significant distances, seen here:

It was invigorating to throw the Banda knives because their aerodynamic qualities were so clearly superior to the others tested.

Impact Test

After launching these knives across the yard, we threw some at a tree at close range (only five yards) to see if they would pierce the bark and stick in the tree or fall to the ground. For this test, every knife was thrown overhand, and because of the risk of damage, the process wasn’t repeated as many times as our field tosses. Many knives hit the tree and fell to the ground, but knives from each group successfully stuck. For the F-types, one of the large Lakas stuck in with its topbranch piercing the bark. This was quite a surprise because the edges aren’t sharpened at all – the blade is simply large and heavy enough to be dangerous even with dull edges. For the Z-types, both Nzakaras stuck, and for the compact throwing knives, two of the Mabos and the Ngombe stuck.

Unfortunately, this impact test produced our only casualty of the day, as one of the Mabos suffered a complete fracture of the crown.

In appreciation of this blade that was sacrificed for the sake of our curiosity, Bobbi took the broken crown, wrapped it in new materials, and created an entirely new and fearsome dagger, and I kept the bottom section to display in my home, still presented as a work of art.